Remembering Jimmy

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

~often attributed to Mark Twain

It’s déjà vu all over again.

~Yogi Berra

Coming from a line of collegiate historians, I often see parallels to the past in current events. Sometimes those links seem strained, but other times they seem quite real and urgent, as they do today. Last month, preparing for my appearance on an investment panel at a regional conference, I expressed my concerns as follows: How do you protect your clients when the geopolitical situation parallels the 1930s, the US economy feels like the 1970s, and the American political landscape resembles the 1850s?

I began my career in the investment business when Jimmy Carter was president. Those were depressing times in ways that young people today have trouble understanding. A few reference points:

• The combination of persistent inflation and slow economic growth gave rise to a new word, stagflation.

• In Carter’s last year in office, during his reelection campaign against challenger Ronald Reagan in 1980, inflation hit an annualized rate of 18%.

• The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in the most significant armed expansion of communism since the Korean War. Many observers of geopolitics believed the democratic West was in terminal decline, destined to lose the long twilight struggle to international communism.

• During the decade of the 1970s, inflation averaged 8.0% while the S&P 500 returned only 4.4%. In real terms, the stock market lost money for an entire decade.

• The job picture was bleak. For graduates with degrees in liberal arts like English or (as I had) history, the joke was that your preparation for your first job was to learn to say, “Would you like fries with that?”

As the depressing 1970s came to an end, President Jimmy Carter was the embodiment of the national malaise.

How much of all this was Carter’s fault? Certainly not all of it. Inflation had been a growing problem since the early 1970s, when Nixon was president.

A Lost Decade for Stocks & Bonds

The 1970s were a grim period for investors. In 1980, Forbes magazine’s annual Honor Roll of Mutual Funds profiled a dozen funds, mostly mutual funds and one closed-end equity fund. These were the very best diversified vehicles available to the investing public, the absolute cream of the money management crop.

Only one of them, the closed-end Japan Fund, had a return in two figures, with an average annual total return of 10.8%. Think about that. Only one investment fund of the hundreds available to US investors was able to return over 10% per year to its investors, during a decade when the inflation rate averaged 8.0% per year. The second-best investment in the 1970s was the Templeton Growth Fund, a global value-tilted mutual fund that had most of its assets in Japanese stocks. It returned just under 9%.

With inflation and interest rates both rising at the end of the decade, bonds were a disastrous investment. When interest rates rise, new bonds are issued at higher rates, and old bonds paying less lose value. In the late 1970s, I remember swapping bonds to capture tax losses that clients could use to reduce their taxable income. In some cases, we did this for several years in a row as rates went higher and higher.

What did work during the high inflation years? Oil drilling and income programs, Sunbelt new construction real estate, commodities trading strategies. All of these performed well during the period of accelerating inflation, and all crashed and burned when inflation was brought under control. In many cases, investors lost 100% of what they’d put into these inflation hedges.

By the middle of Reagan’s first term, as inflation was brought under control and interest rates began to decline, the US stock and bond markets began an 18-year bull market that continued into the first quarter of 2000.

The three biggest takeaways from the investment experience of the 1970s:

• Avoid exotic investments that are sold as inflation hedges, especially those with high costs and structured in non-liquid vehicles.

• Keep your core investments in broadly-diversified, high-quality equities. They may underperform for years, but they won’t go away, and on the other side of the inflationary episode they offer the best chance for recovery.

• The most effective diversification during the bad years is unlikely to be gold or commodities, but rather quality equities from outside the US.

Why Inflation Sucks

Fast-forward to 2022. Why have investments performed so poorly year to date? Today, both consumers and investors are rightly concerned about rising inflation. With the economic and political costs of fighting it perhaps not yet fully realized, it’s worth remembering why inflation is so problematic.

The higher the rate of inflation, the less clarity we have about the future, and the less we’re willing to take risks today that may pay off in future years. Since future returns are discounted at higher rates, current valuations are depressed. Inflation punishes savers and rewards borrowers, at least until rates spike in an attempt to bring inflation down, and borrowers are priced out of the market.

While inflation is bad, hyperinflation is ruinous. Hyperinflation is triggered when folks become unwilling to hold currency longer term. The transition from relative price stability to inflation and then to hyperinflation can be much faster than you would intuitively think.

Given the stakes (hyperinflation destroys both economies and democracies), once inflation starts to heat up, responsible central bankers have no prudent choice but to do whatever is necessary to stamp it out. The higher the rate of inflation, the greater the cost of controlling it, in terms of both unemployment and loss of gross domestic product.

“Whatever is necessary” is a world of short-term hurt, and the pain is usually ruinous to the political ambitions of whoever is in power at the time.

Carter’s Big Mistake

The high inflation that cost Carter reelection more than forty years ago was largely the result of a profound policy error.

Historically, what presidents do in their own electoral self-interest is to spend their first two years in office clamping down on inflation, at the likely cost of a slowing economy or even a recession. This usually means the sitting president’s party loses the midterm elections. But with inflation under control, fiscal and monetary policy can combine to stimulate a strong economy during the president’s reelection campaign.

Carter did exactly the opposite. He was elected on a platform promising to return the sluggish US economy to full utilization. His mechanism was a policy of loose money. He put a businessman, G. William Miller, in charge of the Fed, instead of a central banker. Fed Chairman Miller pumped up the economy by expanding the money supply in the first two years of Carter’s presidency, with the predictable result that inflation spiked during the 1980 election campaign. The prescription for controlling inflation is high interest rates and tight money, which are the last things any president wants in an election year.

Carter resisted taking action until the currency markets gave him no choice. In the fall of 1979, with the US dollar in free fall, down more than 25% against the Deutsche mark, British pound and Japanese yen, he was forced to act. He replaced Federal Reserve Chairman Miller with the respected and credible head of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, Paul Volcker, a notorious inflation hawk.

Volcker raised interest rates on Treasury bills and contracted the money supply. Interest rates spiked, Carter lost reelection, economic activity fell sharply, with the worst recession since the Great Depression bottoming out in 1982…and inflation began to fall.

Carter’s error on inflation was not novel. Most wealthy economies try to separate the central bank from the elected administration, because elected politicians naturally have a relentlessly short-term focus on the next election. Sound economic policy by its nature must have a longer-term perspective.

A Tale of Two Presidencies

The four most expensive words in investing are, ‘This Time, It’s Different.’

~Sir John Templeton, legendary global value investor

There are some clear parallels between Democratic Presidents Jimmy Carter in 1977 and Joe Biden in 2022. Both took office with Democrats in control of both houses of Congress. Carter took office with inflation already high and sent it out of control with a remarkable policy error. Biden took office with inflation persistently low and sent it out of control, to the surprise of some mainstream economists, with an avoidable policy error.

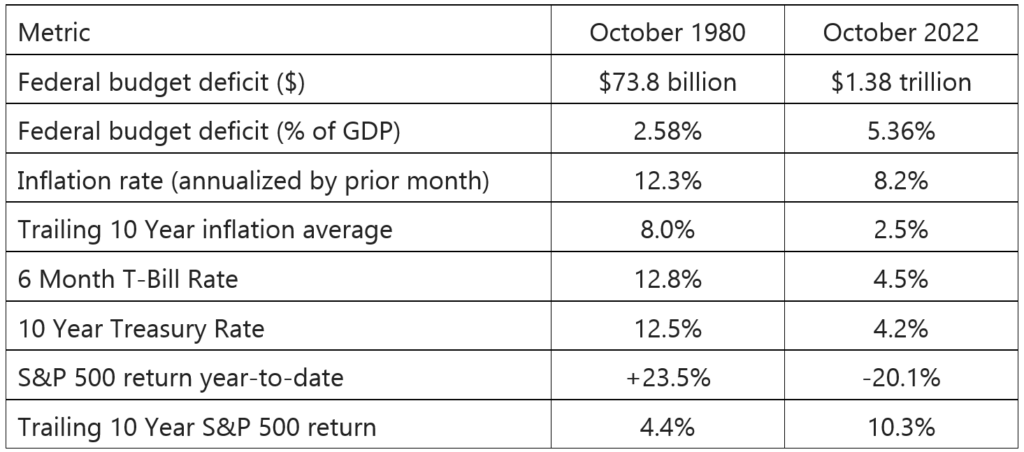

Let’s compare the situation today just after the midterm elections to the situation in 1980, during Carter’s last year in office, when he was running for reelection against Ronald Reagan:

In one sense, the economy was way worse under Jimmy Carter. Inflation was higher, and so were interest rates.

But in another sense, our situation today is in some respects more challenging. Our cumulative debts in relation to the size of our economy are an order of magnitude higher. Our budget deficit is twice as high compared to GDP.

Over the last ten years, stock market returns in the US have been high right through the end of 2021. Today’s stock market is almost four times as expensive in relation to earnings as was the US market at the bear market bottom on August 19, 1982.

As the 1980s began, a decade of high taxes and government expansion had strangled the world economy, while expansive monetary policy had driven inflation ever higher. The cost of controlling the inflation of the 1970s was a severe recession. At the bottom of that recession, stock and bond prices were lower than at almost any point in the entire 20th century.

Within four years, the combination of lower taxes and reduced regulation triggered an economic boom, and those extreme low stock and bond valuations set the stage for the longest stock and bond bull markets in human history.

Today, the Fed’s policy of raising interest rates at risk of a recession is designed to prevent us from ending up in a 1970s-like inflationary episode, where the costs of controlling inflation would be much higher. The stock market is in a bear market, bond prices have fallen sharply, and the economy may already be in recession.

One of two things will happen next:

• Controlling inflation will require even higher interest rates, causing in turn a deeper and longer recession. In this scenario, stock prices may have much further to fall.

• The Fed’s policies may already be close to bringing inflation under control, and interest rates will need to rise only a bit higher before price increases begin to moderate. In this scenario, we may have already seen the cycle lows.

In either case, whether we’re heading for a deeper recession or already past the worst bad news, stock prices is the US remain unusually high by historic measures, and future returns will be constrained.

As a Reagan Republican, I’ve never been a fan of Jimmy Carter, nor of the senior senator from nearby Delaware, now President Joe Biden. But having taken this deep dive into the economic history of the 1970s and also the recent past, I feel compelled to say that both Carter and Biden, after making serious mistakes early on, acted responsibly and against their own interests in starting to control inflation. Despite the costs to their electoral hopes, neither let short-term electoral concerns trump the long-term financial viability of our nation.

Speaking of Trump, can you image the former president having to make a similar call in an election year, with a recession looming and a Fed chairman as compliant as Bill Miller? The stuff of monetarist nightmares.

As a disgruntled Republican who hasn’t been really happy with the any of the occupants of the White House since 1988, my principal reaction to the last two presidents (Trump, Biden) is that bad outcomes result from having our national economic policy driven by people who aren’t smart enough to run corner lemonade stands, never mind the economic policies of the world’s superpower.

Strategy & Tactics

So what are the implications for investors?

• In a time of short-term policy errors and resulting economic challenges, the most vital response is to remain relentlessly focused on the long-term.

• Inflation is much more costly to growth stocks than it is to the cash flows of sensibly-priced value stocks.

• Quality common stocks have historically been the best asset class over almost every long-term period, but we need to keep in mind that the long term can sometimes be very long indeed.

• Investments specifically focused on rising inflation rarely produce competitive long-term economic returns, and their risks are significant. Better to suffer a period of lower returns on quality assets than buy trendy assets that might go to zero.

• The global economy is linked, more so today than in 1980. In the short run global markets tend to move in sync, but in the intermediate to long term, global financial markets can diverge significantly. Overseas opportunities can sometimes offset domestic reversals.

• Things could get much worse. But remember that the worse they get, the bigger the long-term opportunities for resolute and focused investors. The biggest opportunities come after inflation peaks and before the economy bottoms out.

The decisions I made together with my clients in the early 1980s helped many families to build transformative wealth over the following decades. Remain disciplined and patient, look for opportunities amid despair, and we’ll all get through this together.

By James S. Hemphill, CFP®, CIMA®, CPWA®/ Managing Director & Chief Investment Strategist

Jim has been a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional since 1982. Jim specializes in complex wealth transfer and retirement transition strategies and coordinates TGS Financial’s investment research initiatives.

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by TGS Financial Advisors), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this article will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this article serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from TGS Financial Advisors. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. TGS Financial Advisors is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of this article’s content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the TGS Financial Advisors’ current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request.