A More Realistic and Useful Accounting of Net Worth

Over the last two years, we’ve developed an educational channel for physicians that’s taken the form of a video series and a workshop series, both designed to introduce key financial concepts and strategies. Pulling this content together has helped us to hone our observations about what works in personal finance and to build a systematic program of advice that addresses the unique circumstances of physicians.

In the process, we realized that many of the concepts apply powerfully in our own financial lives. Even those of us who’ve been advisors for decades have been inspired to reflect on some of the financial choices we’ve made. For instance, my wife and I now refer to our home as The Big Stupid House. If we could go back in time, we’d probably buy something smaller and pre-owned instead. (Don’t tell our kids. They’re very attached to the home they grew up in.)

It can be a great shortcut to learn through the experiences (and mistakes) of others. Indeed, some evolutionary biologists hypothesize that the survival benefit of larger brains may come primarily from the ability to learn from the mistakes of others. If a fellow-caveperson tells you about their experience of being gored by a wild boar, you stand to gain boar-management strategies without suffering the trauma yourself. The same kind of advantage can be found in your modern financial life.

One of the key concepts we’ve begun to discuss with clients is that of functional wealth. We developed this term to communicate the difference between “good assets” and “bad assets.” Some assets put dollars into your pocket on an operating basis (equities), while others take dollars out of your pocket (art, homes, speedboats, and expensive hobbies). While this is not a new idea in and of itself, what can make it powerful and accessible is the use of a functional balance sheet rather than a traditional balance sheet. A functional balance sheet allows for a more realistic and useful accounting of net worth.

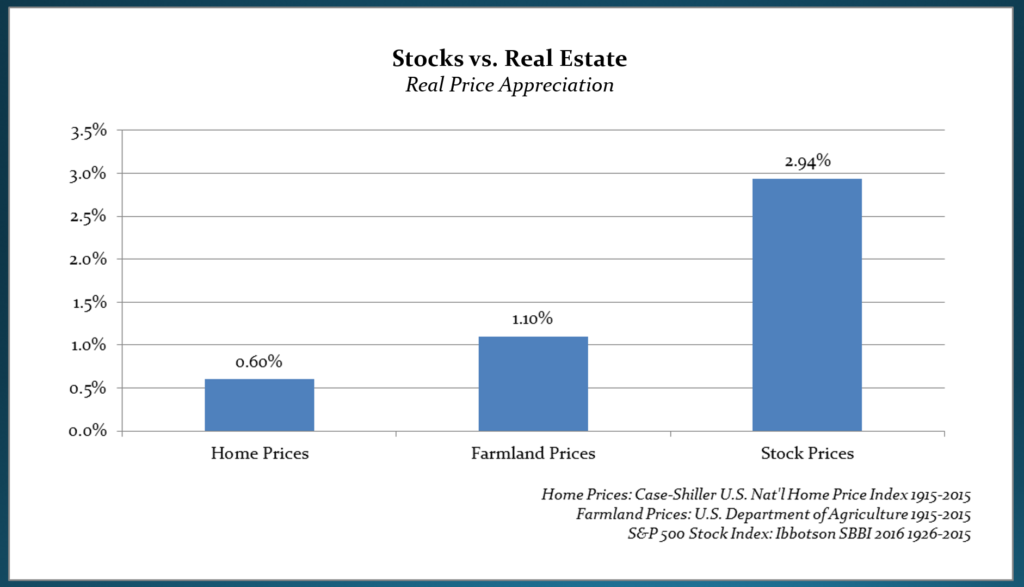

When we use this insight, and add to it the research of Robert Shiller on home prices, for example, we can begin to construct a perspective that’s useful for making decisions about savings versus consumption. Consider one data point:

We can use this information to help current and future clients understand the impact of their decisions. Smart planning asks and answers what-if questions: If I buy less house, and instead use those dollars to buy productive investments, how does that affect the education funding for my children? If I sell an unproductive real estate asset and use the proceeds to reduce debt, how might that increase my terminal wealth at retirement?

Smart planning asks and answers what-if questions: If I buy less house, and instead use those dollars to buy productive investments, how does that affect the education funding for my children? If I sell an unproductive real estate asset and use the proceeds to reduce debt, how might that increase my terminal wealth at retirement?

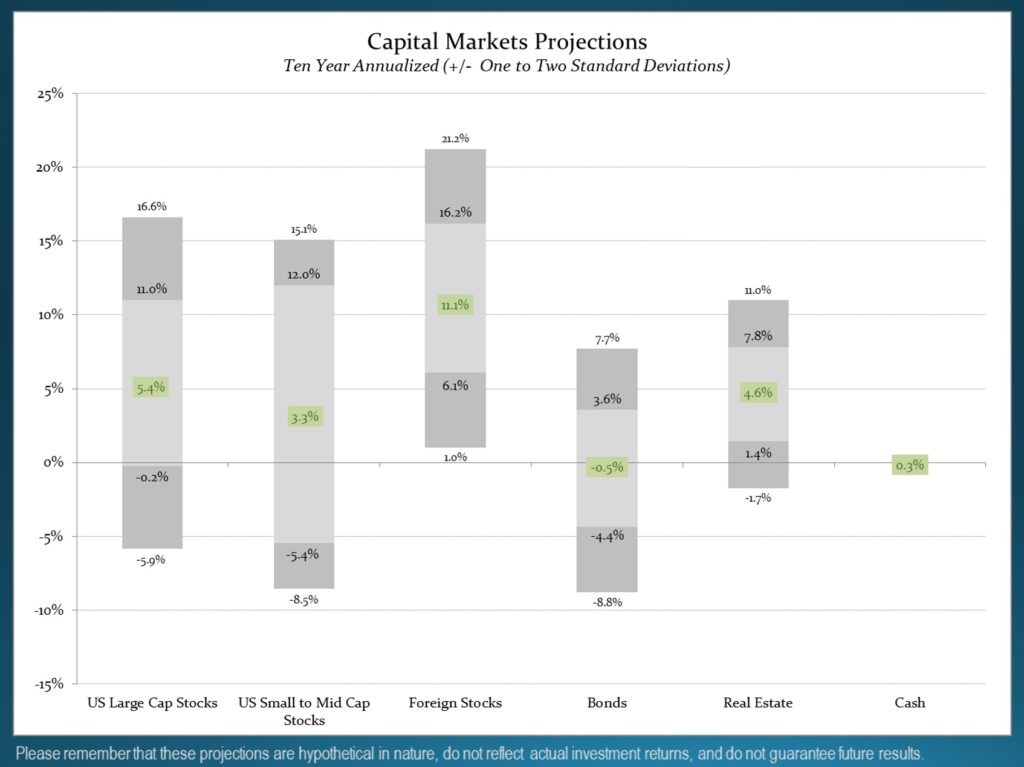

Being able to capture the change in functional wealth is crucial, because year-by-year returns on residential real estate and investments are highly variable and unpredictable. For example, selling a high-cost vacation home in order to buy an S&P 500 Index fund might result in less money in any given year. We can’t predict short-term results, but we can do an informed analysis about the long-term benefits of an increase in functional net worth.

Obviously, these are only illustrations using assumptions we believe to be reasonable. They can’t be guaranteed, and will surely differ materially from the precise real-world numbers on net worth at specific intervals. The purpose of running these numbers is to inform our decision-making.

I’m curious. Does the idea of functional wealth resonate with you? Would thinking about your financial choices in this context help you make more intentional decisions? Please email me and let me know your thoughts.

By James S. Hemphill, CFP®, CIMA®, CPWA®/ Managing Director & Chief Investment Strategist

Jim has been a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional since 1982. Jim specializes in complex wealth transfer and retirement transition strategies and coordinates TGS Financial’s investment research initiatives.

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by TGS Financial Advisors), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this article will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this article serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from TGS Financial Advisors. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. TGS Financial Advisors is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of this article’s content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the TGS Financial Advisors’ current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request.