Market Rotation: The Last Shall Be First

In December 2021, I spoke with a friend about the excesses of tech stock valuations. I commented that Tesla, with a valuation equal to that of the nine largest carmakers combined, was priced as if Tesla was the company that would sell every car in the world at some future date.

My friend thought about it and then replied, “Why is that unreasonable?”

I’ll try to explain my thoughts about Tesla with numbers. Keep in mind that this type of conversation was pretty typical during the period leading up to the high-water mark for tech stocks in 2021.

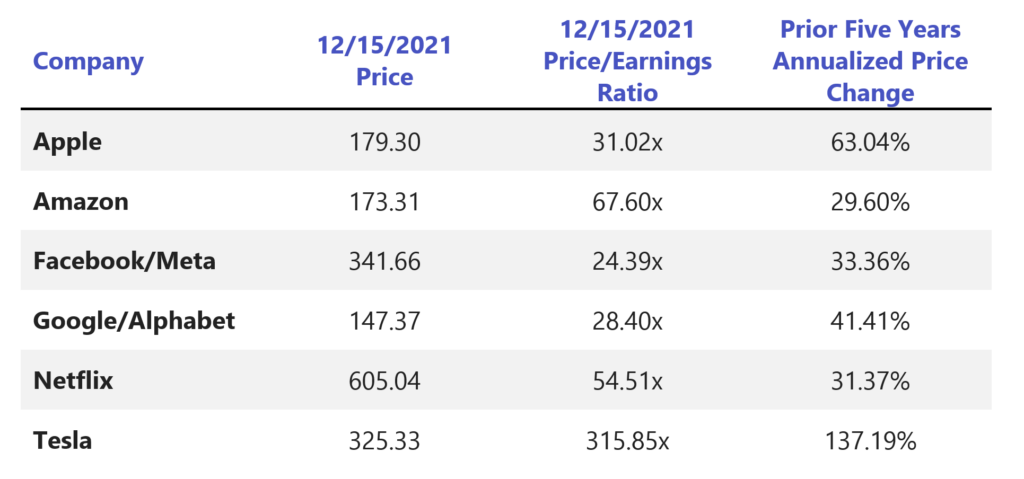

The extreme valuations of a handful of tech companies have been a topic of our Market Comments for years. Here’s a table showing the prices of the usual tech suspects as of December 15, 2021, and the compound growth of their stock prices over the prior three years:

These are some simply amazing numbers. Sky-high prices brought about by explosive business growth. Premium price-earnings ratios, justified by fast-growing earnings. Potentially life-changing investment returns.

An implicit thesis supported the sky-high valuations of Google/Alphabet, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Tesla: these were not just successful businesses with fast-growing sales and earnings; these were unique enterprises with business models so robust as to be considered immune from business setbacks and competitive pressures.

To use a phrase I first heard about oilfield services companies way back in 1981, these tech giants were “one-decision stocks.” Buy them, hold them forever, and the profits would flow without end.

If one accepted the idea that these tech titans had perpetual advantages, and observed the extraordinary returns seen above, the ridiculous prices would seem justified. At least that was the theory.

We disagreed.

What a difference a bit more than a year made! Last year, two fundamental changes upended the rosy picture above:

♦ Higher inflation prompted the Federal Reserve to sharply increase short-term interest rates and the bond markets have driven longer-term rates higher as well. Higher interest rates equal higher discount rates, which means those projected streams of future earnings increases are worth much less today than they were 18 months ago.

♦ Even more important, those projected ever-growing earnings proved an illusion, even for dominant tech companies. Several of the tech titans have suffered meaningful erosion of their economic models. Those projected streams of future earnings increases didn’t happen.

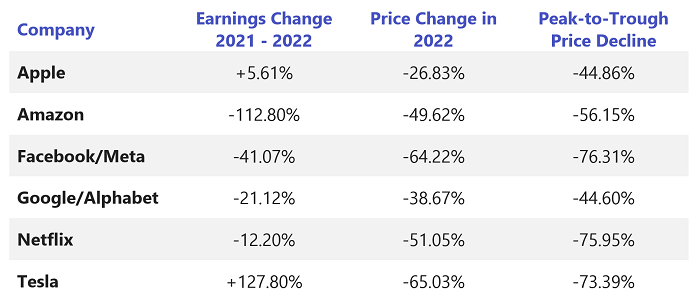

Since September 30, 2021, here are the changes in earnings of those same tech names and the peak-to-trough declines in their stock prices:

Every one of these dominant tech companies declined in value by anywhere from 44% to over 75% peak to trough. All but two of them (Apple and Tesla) suffered declines in earnings. Amazon’s earnings actually disappeared and the company lost money. (This is not unusual for the dominant online retailer, which since its founding has prioritized growth over earnings. Jeff Bezos might say this loss was a feature, not a bug.)

In every era, there are companies, sectors, or investment themes whose stocks dominate the markets. In the 1960s, it was IBM and Xerox; in the early 1970s, the Nifty Fifty growth stocks; in the late 1970s and early 1980s, oil and oilfield service companies; in the late 1990s, tech stocks; and in the late 2010s and early 2020s, tech again.

Chasing the hot sector works until it doesn’t.

In the second half of the 2010s, loading up on tech was hugely profitable, as tech earnings grew quickly and tech stock valuations rose past the absurd and into the delusional. A good example is electric car and battery maker Tesla. In late 2021, Tesla shares were trading at 315x earnings, 25x sales, and 200x free cash flow. Tesla was worth more than the world’s seven largest car companies combined, which in total sold 56x times more cars.

Tesla fanboys, worshipping at the altar of Elon Musk, believed the price was not just defensible, but reasonable. Whether they realized it or not, their ownership of TSLA embraced the proposition that Tesla would keep growing 50% a year forever, until they eventually controlled the entire world car market.

This belief was never really defensible. The reality is that Tesla competes in the global automobile market, a historically-cyclical, capital-intensive, price-competitive sector with overall excess manufacturing capacity. It’s a sharp-elbowed marketplace where all the big players have plenty of marketing and engineering expertise.

To take a single example of Tesla’s competitive challenges, Elon Musk has promised full self-driving capability every year since 2013, but has never delivered. Recently Mercedes Benz announced Level 3 self-driving technology, while Tesla remains stuck on Level 2.

It seems all those German engineers weren’t sitting on their hands waiting patiently for Tesla to eat their collective lunches.

A friend of mine recently totaled his Tesla Model S. He relied on Tesla’s Level 2 self-driving feature, and read an article on his phone while his car drove 70 miles an hour on a California freeway. He was hit by a merging truck, rolled and totaled his car, and was very fortunate to walk away.

His new car is a Hyundai hybrid, despite the fact that Tesla has slashed prices of its automobiles for the first time, trying to revive lagging sales.

Of course, it’s not just Tesla.

Facebook became Meta, betting that a change from social media advertising platform to key player in the emerging virtual world would save their business. Unfortunately for Zuckerberg and company, nobody much cares about the new Metaverse. Their advertising model is collapsing, their earnings have fallen by half, the price by 75%, and it seems they have no idea what to do. Except to fire another 10,000 employees, which they did in mid-March.

There’s an internal contradiction in the always-tech thesis. For the stunning valuations to be defensible, tech must be simultaneously a high-growth sector and a high-stability sector. Businesses must be dominant, fast-growing, and profitable…yet somehow remain largely immune from successful competition.

That combination is unlikely. There are high returns to successful innovation, but those high returns attract smart people and hungry capital to tech startups trying to take market share away from existing tech businesses.

This won’t be the last positive tech cycle we see in our investing careers, nor the last tech bubble, nor the last tech collapse.

There will always be a next-generation tech breakthrough. My guess is that the best-performing stock over rolling five-year periods will usually be a technology name in most years for the rest of our lives. But it will rarely be the same tech name.

The next cycle’s tech champions usually emerge from somewhere we don’t really expect, and are seldom the major legacy players of the last cycle. Identifying those emerging tech superstars will be hard, and most tech startups will be disappointments. Knowing when to change horses will be an unending challenge.

Our job is to protect, maintain, and enhance your wealth for as long as you live. Let me say that again, for as long as you live.

Thus our principal investing bet will remain the same, just as it has been since our firm’s founding in 1990: Buying the future cash flows of publicly-traded businesses across the world is the most durable way to grow, maintain, and protect real wealth across a lifetime. Buying more cash flows per dollar invested will usually be better than buying less cash flows. That is the central thesis of value investing—that buying less exciting businesses at lower prices is likely to be, in the long run, more profitable than buying more exciting businesses at elevated prices.

Over almost a century of stock market data, value stocks have outperformed growth stocks by an average of 3.7% per year. Always in the past, a period of growth dominance has been followed by a period of value dominance.

♦ From 1930 to 1940, growth beat value by 6% per year. From 1940 to 1950, value beat growth by 12% per year.

♦ From 1995 to the stock market peak in February 2000, growth beat value by 11.5% per year. From the 2000 peak to the subsequent peak in 2007, value beat growth by 8.5% per year.

♦ From 2015 to 2021, growth beat value by 8.3% per year. In 2022, value beat growth by 24.2%, and the big tech stocks profiled above did much, much worse. Our portfolio tilt toward value stocks was relatively unprofitable for six years, but was really helpful in the 2022 bear market.

What comes next?

So far in 2023, growth and tech are enjoying a remarkable rebound, with price increases much larger than for value stocks. Tesla, Meta, even Bitcoin are up sharply. We’re back to a “risk-on” environment.

Might this be the beginning of another five-year run of tech dominance?

Of course, this is an unanswerable question. The future is always an undiscovered country. To us, it seems likely that growth is enjoying a dead-cat bounce, and that value will outperform growth over the coming decade.

We could be wrong. What we’re confident about, however, is that value returns, unlike growth returns, are economically predictable enough to form the rational basis for giving advice to our clients about their lifetime finances.

Our job is to protect, maintain, and enhance your wealth for as long as you live. Let me say that again, for as long as you live. Not to beat the market this week, this month, this year, or even for the next decade. It’s to deliver adequate risk-adjusted returns for an entire investing lifetime.

We hope yours is a long, happy, and healthy lifetime, free from worries about running out of money, for you as much as for ourselves.

As always, we’re grateful for your business, your loyalty, and your friendship.

By James S. Hemphill, CFP®, CIMA®, CPWA®/ Managing Director & Chief Investment Strategist

Jim has been a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional since 1982. Jim specializes in complex wealth transfer and retirement transition strategies and coordinates TGS Financial’s investment research initiatives.

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by TGS Financial Advisors), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this article will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this article serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from TGS Financial Advisors. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. TGS Financial Advisors is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of this article’s content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the TGS Financial Advisors’ current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request.